Two weeks ago, I failed.

It was not the light-weight kind of failure: the "oops, my bad, let's fix it, no big deal." This failure was not the difference between 70% complete and 95% complete.

This failure was the kind that crippled my self-confidence, that unleashed my cruelest shame gremlins, that permeated doubt into every aspect of my life. It was the kind of failure that became more about what it represented than what it actually was.

As a culture, we don't often speak of failure, at least not the kind that totally blind-sides us, leaving us shaken to our core. More concretely, we do not talk about how we felt when it happened. Failure is sort of lionized in the design and entrepreneurship communities. There's a blasé attitude about the associated emotions; they are something merely to be glossed over, for they do not mean anything substantive. We do not readily admit to feeling lost, alone, and afraid. It might even seem unprofessional (gasp!). I certainly questioned the wisdom of writing this post, lest I be perceived as weak or emotional.

I find this unfortunate. We are giving the silent treatment to an inevitable fact of life; more importantly, we're all susceptible to the emotions that come part and parcel with it. We all feel it, why not acknowledge it?

My failure.

My failure occurred over a two-day sprint to produce a solo project. I came in with a solid project idea, the scope of which seemed manageable. It would be built using technologies we had already learned about, to solidify my understanding.

The past several sprints have exposed us to many interesting ways to architect a full-stack application. Each one takes a different tact, they all seem to have their strengths and weaknesses. Wanting to learn from these examples of professional code, I tried to build my new app as a conglomeration of these previous samples.

Building a Frankenstein app proved far more difficult than anticipated. While I could reason my way through all the samples, I could not establish sufficient mastery to fluidly tie them together. I couldn't hit my stride, get into the zone. By having the "right way" close within reach, I never challenged myself to solve each problem myself. Every new task required yet another scouring of the previous solutions. It almost felt like cheating, the way I would resort to the examples, that I wasn't learning anything. Meanwhile, I was going terribly slowly.

By the time dinner rolled around, I perceived myself to be dramatically behind the rest of the cohort. I was suddenly feeling in over my head, and the spiral started.

The outcome.

By the end of the project period, I had very little to show. Some barebones HTML plus a hardly functioning backend; the result was considerably less than originally planned. While "falling short of original scope" is a commonplace experience in software engineering (indeed, part of the project goal was to experience this very fact), I was discouraged because I still felt the original scope was reasonable.

The outcome of the project felt underwhelming. Which comes as little surprise, given the impact on my productivity from lost confidence and time spent agonizing over my performance. I felt as though I had entirely missed the learning objectives and didn't learn anything technical in the process. My app was a paltry offering of what I believed to be my actual potential. While others presented creative ideas and even more creative execution -- revealing aspects of their design choices in getting to MVP complete -- I had very little to show.

We all make comparisons.

I was ashamed. Solo projects can really feel like a representation of yourself. We put in our heart, we make it stand for something. When I produced a paltry project, it stood for more than what it was in fact -- it reflected poorly upon me, my character, my potential. I take pride in my craft, I want to do well at the activities to which I apply myself. I have always been in a never-ending competition against myself. Usually, I fare pretty well, though often at the expense of friendships, sleep, or free time. But woe be to me when I can't live up to my own (perhaps unrealistically) high standards of performance.

The second pain point was in the inevitable comparison I made with the rest of my cohort. They all produced such wonderful, inspired, creative projects. I was thoroughly impressed. This was a truly wonderful fact, though it hurt internally all the more. The procession of students giving their quick presentations of their projects became an instrument with which I could flog my self-confidence: you are outclassed, you do not belong, you will not succeed.

Comparisons are a tough nut to crack. We all recognize the poison it represents. One of my favorite lines about comparisons comes from Desiderata by Max Ehrmann:

If you compare yourself with others, you may become vain and bitter,

for always there will be greater and lesser persons than yourself.

Despite the unquestionably negative influence of making comparisons, it is so easy to do. We are all taught comparison at an early age, we grow up in environments that unwittingly rank us against our siblings and peers. We often do it without realizing, particularly in strenuous environments. We're social creatures, we want to know if we're the only one struggling or falling behind. It's easy to look externally to validate our success or difficulty.

It's very easy for us to compare ourselves to others, particularly in areas closest to us. Be it art or engineering, we unconsciously look to others to gauge how well we're doing. Even "comparing against your ideal self" actually involves others, for the context of your ideal self -- of how good can you really be -- is informed in part by those around you. There's always context provided by other people; on some level, comparison is, perhaps, inevitable.

They have a phrase in yoga: "focus on your own mat." Free yourself from competitiveness and bring attention to your own journey. What does it matter how others are doing, for all journeys in learning are non-linear. Appreciate where you are and look forward to where you might go next. These are concepts I leverage heavily in my own teaching philosophy. Do as I say, not as I do.

It is so, so, so hard to not compare. What can one do after the comparison is made, after the spiral has begun? Despite my proactive efforts to draw myself out of the negative feedback loop -- a self-aware healing response I have only recently developed -- it was not possible to wrench me away from the muck.

People don't (usually) engage in a craft or profession to be the best. Whatever the reason, it generally has little to do with external validation. Through the learning process, we sometimes lose our grounding: we forget that which connects us to the field, what makes us love what we do. Focusing on these reasons may be the ticket out of such spirals by drawing attention to our internal sources for joy in our activity, giving us the courage to rise to the challenges we face.

Loving what you do is the key to happiness, not attaining a certain level of proficiency. It's easy to think proficiency will get us a good job and lead to happiness. More critically, we believe we must be more proficient than our peers, since we're all in competition for the same opportunities. Our culture is one obsessed with scarcity -- of food, of opportunities, of love. We are inculcated to believe that we must be the best in order to win in the professional realm. You can see it in the narrative of job seekers anywhere: use whatever strategies possible to "rise to the top."

It would be factually inaccurate to say that competency does not impact availability of opportunities. People do not get into Google by being par software developers. However, while the impact on available opportunities may be real, the impact on our "success" and our happiness is decidedly fictitious. Obsessing over our proficiency relative to others only hurts our sense of success, for there is a toll exacted by seeking external validation.

We all have bad days.

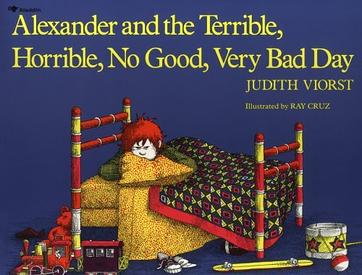

We all have terrible, horrible, no-good, very bad days. These days are way more pronounced in high-pressure environments -- there's no way to escape, to walk away and walk it off and come back in a natural time when the emotional triggers and hormones wear off.

You cannot afford to have a bad day, so you compress those emotions into a little box: the fear, the self-doubt, it all gets stowed away, because you need to be able to focus, to perform. Eventually, though, it will find an outlet, whether you provide it or not.

When we fail, all we can do is acknowledge that it happened and keep moving forward. Our shame gremlins will latch onto such events and try convincing us that it's evidence of our inevitable failure in life. Part of learning to fail is dealing with these reactions, feeling the emotions while staying the course. We all have our gremlins; what makes the difference is what we do with them. These experiences make us resilient, this ability to feel discouragement genuinely while never giving up on our path. To resolutely trudge forward certain of ourselves, even while that little voice trolls us in the back of our head.

We all face discouragement. In society, it's a shameful thing to talk about. We may speak nostalgically of the times we messed up; but to admit feeling discouraged or unconfident is a big no-no. We are not supposed to acknowledge what it feels like to fail, what it's like to question ourselves. If we do share, the response from others is generally to shut it down quickly: "No, you're fine, you'll do great, stop being so hard on yourself," etc. How unfortunate, for I think we often want validation of our feelings (discouraged, crummy, inept, whatever) in those moments: an acknowledgement that what we're feeling is natural, real, and normal.

So, let's talk about it.

When hitting a spiral, the whole world can collapse upon itself. For me in that moment, I completely lost perspective: my failure was the only reference point for my life, the only benchmark by which I was evaluating my success in the world. It can be so, so hard to step away from that reality and gain perspective. We're in a deep, dark hole and feeling terribly alone.

That's part of what makes human connection so powerful. Dr. Brene Brown speaks of it quite movingly in a famous TED talk. When we have someone climb down into that hole with us and say, "Yeah, I feel you, I've been there too," we are reminded that this hole is natural to the course of human life and somehow we still get on alright. That's real empathy. (Pause to let you watch the video -- it's so worth it.) Ultimately, it was empathy that helped me climb out of my hole.

Such interactions did not provide solutions or impossible guarantees (e.g. "You should do X", or "You'll be fine!"). Instead, they reminded me that what I was feeling made sense ("You're not crazy for feeling this way") and that they've felt it too. On an unconscious level we get the message: these are people I respect, people doing good things in life, and they've been in the same place before! Maybe I will be okay after all, since they are too. Empathy shows us that there really is a light at the end of the tunnel by revealing the fact that we've all been in that same tunnel before. So while it may be cold and scary right now, we can keep trudging forward with the faith that, at some point, we'll come out of it.

Returning to baseline

Allowing ourselves to be fully present with feelings surrounding perceived failure is a form of self-care. We recognize our emotions as legitimate, our reactions understandable. Not doing so places judgment on our emotions and creates a new point upon which we can negatively rate ourselves. Once we do so, we can move on from the feelings and into a new frame of mind.

It is tempting to think of the dark hole of despair as fundamentally bad. However, that hole is part of what makes us human. The beauty of our humanity shines through when we can be in that hole, feeling those emotions so genuinely, while at the same time deeply believing in our ability to persevere and thrive. This duality we hold within us provides contrast for our emotional highs and lows; one extreme would seem so much less meaningful or valuable without the existence of the other. Neither defines us by themselves and we are best served welcoming both experiences.

Success and failure represent valuations from the outside. Reveling in either rob us of our focus on doing what we do for joy and meaning. Rudyard Kipling in If: "If you can meet Triumph and Disaster / And treat those two impostors just the same." We do not engage in our crafts to be good (or bad?) at them. Successful and failure are external motivators; what we do, we do for love, we do for ourselves.