A plethora of coding tutorials float around the Interwebs. A sad majority of them suck. This tutorial aims to provide concrete ways to make your own tutorials even better. I'll cover key elements in organizing, composing, framing.

Organization

People like structure, especially coders. Which is why I'm always baffled when programmers write blog posts that have little to none.

Paint the picture.

Open with the reason why they should read this tutorial or what they will learn in the process. Explain in a sentence or two how you will approach the problem. Highlight key concepts or modules you will build out and summarize their interaction. Open with a "once up a time..." to welcome the reader along for the journey you're about to lead them on.

Use structure. Lots of it.

If your tutorial is more than two screens of material sans pictures, you probably need structure. We benefit from grouping our knowledge. How you modularize your tutorial depends on the content, but do your best to keep a consistent them. Whether by abstract concept or concrete product, pick one and stick with it. If you need to break the pattern, do so clearly.

To understand why the above is important, let's take a brief aside on how we store information.

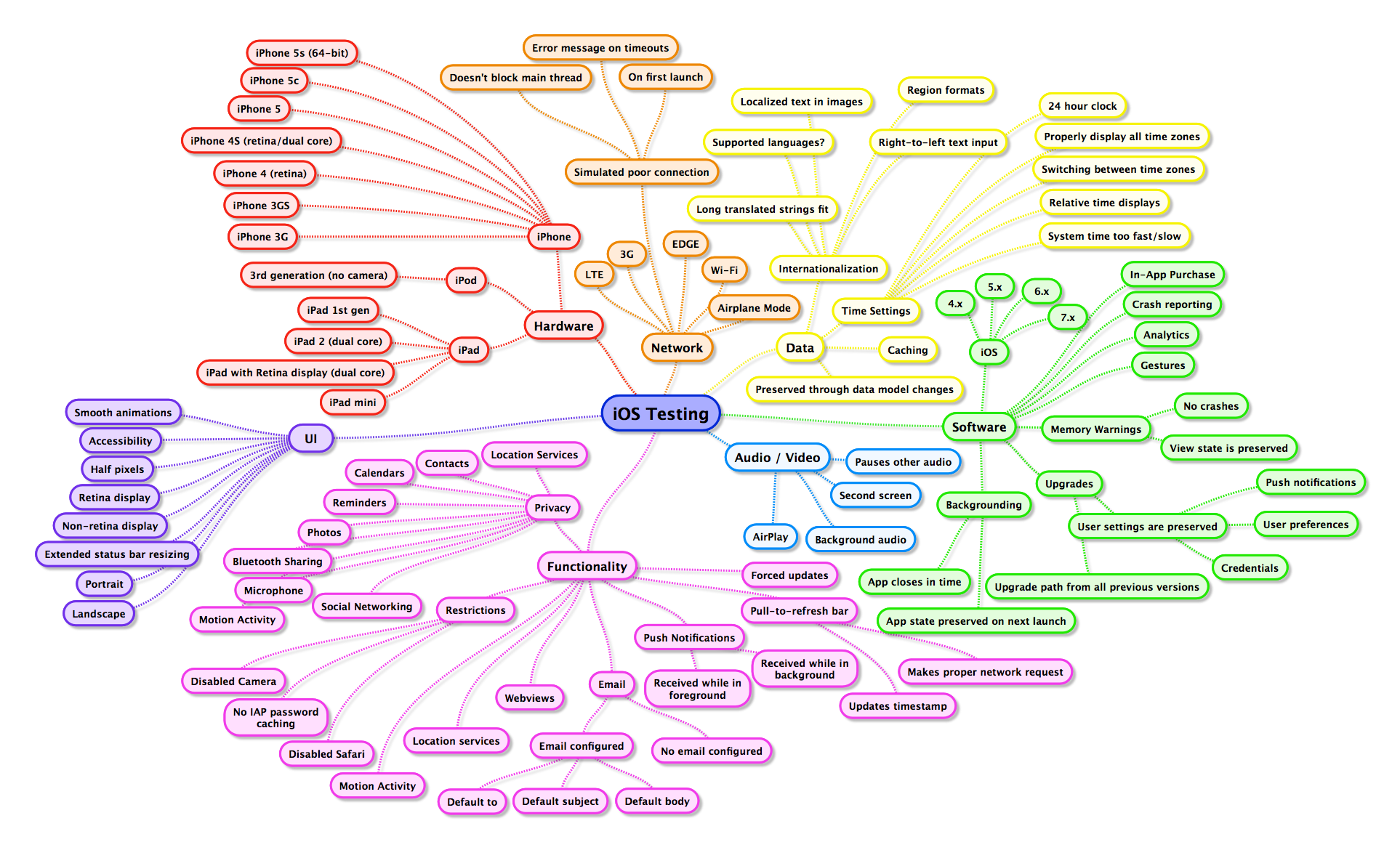

I'm not actually well-researched in this topic, but I've thought about it a lot. I imagine our knowledge is like a web with many interconnected nodes. With clear structure, we can place related nodes closer to another, establishing relationships through proximity. By knowing what pieces huddle together, we can also explore the interactions between groupings.

When information is presented without structure or context, the student is left to their own devices to attempt categorization of the knowledge. We need an anchor, a point to tether this new sub-web of knowledge to our extant mind map.

Remind people of the structure throughout the article.

Some may consider it coddling, I consider it being effective. At the transition points, remind your user of what we've covered, where we're going next, and perhaps even how they're related.

For some, structure will develop organically through the writing process. For others, the structure offers a scaffolding around which content can be produced. Either way you do it, here are some considerations while creating your content.

Content

The goal here is to offer simple tips on improving the quality of your content presentation. I won't go into writing advice here -- that requires its own textbook.

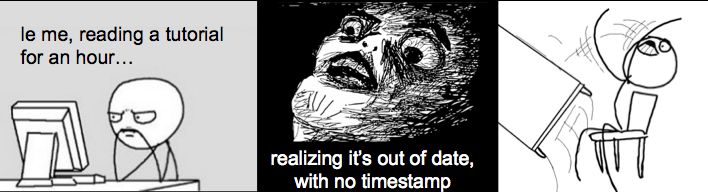

Date your posts.

Date your bloody posts. I am appalled by the dearth of timestamps on blog posts and tutorials out there. Tech moves fast, so readers want to assess the risk of your information being out-of-date before diving in.

Keep it short, analysis first.

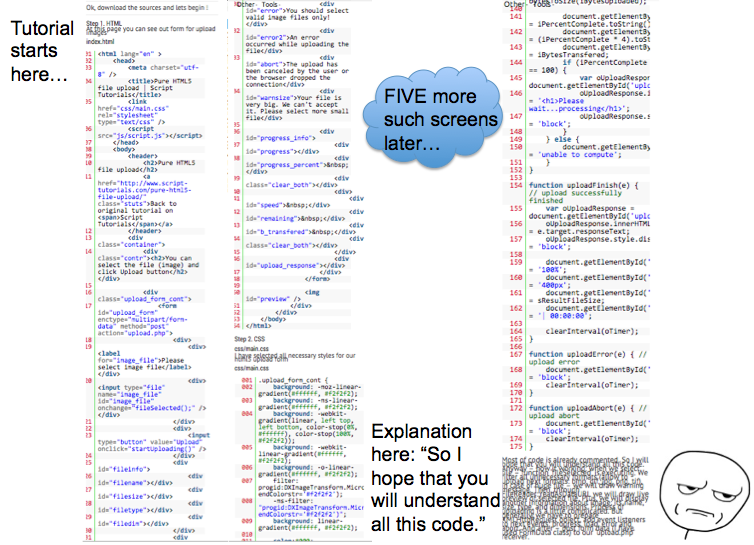

It's tempting to present the code and then write about it. When you do so, you leave the reader suddenly lost in a sea of unfamiliar code.

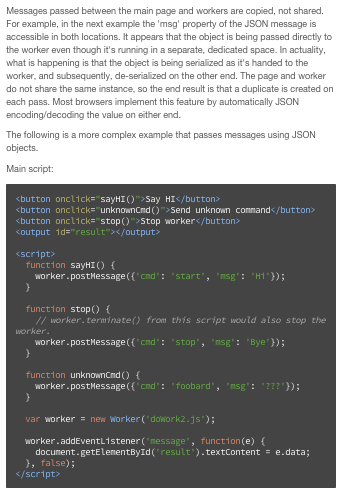

Instead, discuss what you're about to do in plain English, then present the code. People will find it much, much easier to follow. It may be annoying to write things as, "then, inside the web worker object, we ...," but ultimately this works to the favor of the reader.

This one is much better:

Following the advice about "discuss first, then code" will naturally give way to keeping your sections and code snippets succinct. When you have to explain everything first in human language, it becomes cumbersome to describe the entirety of the program all at once. Without indents and objects to keep track of where we are, we must find natural breaking points to present a snippet of code, before moving on to the next piece.

Presenting code in this way will lose some understanding of the context for each snippet. It's a tradeoff, one which I'm willing to sacrifice. You can always post a complete solution at the end so they can see it all fit together. It's much better than hoping for your reader to understanding everything all at once.

Use pictures.

People like pictures. A lot. I suspect that most of you, like me, are not good enough to write for the New Yorker Magazine. Our style is not sufficiently compelling to carry interest for many pages without some visual augmentation. So, do your reader a favor and include some pictures.

Make your code pretty.

I've seen some people take screencaptures of their code (⌘ + Shift + 4 on the Mac), instead of using the default Markdown styling, to make things prettier. I don't recommend this for three reasons.

- It obscures your work from search engines.

- It leaves the 5% of internet users whom are visually handicapped (color-blind, blind, etc.) at a loss. Sad times.

- If you change your code, you'll have to take another screenshot. That's a wasteful workflow. Also, you have to take the photos and upload them.

If you want to show off code, there are two that I recommend: Prism and Syntax Highlighter.

Prism offers a lightweight and customizable solution to highlighting your code. It requires you to host only two files (a js and css file) on your own site. Added bonus for Prism: follow this tutorial to install it on Ghost in five minutes.

SyntaxHighlighter is something like the old guard: been around since 2004. The latest files are already hosted, so you can quickly install. (However, hosting costs money, so the author does ask for donations.) Many, many, many people use it.

I'm now using Prism for my site.

If you want to show off a website concept, use CodePen or JSFiddle. Both allow you to code HTML, CSS, and JS, then creates a live preview. CodePen has the added bonus of being easily embeddable in your post.

See the Pen repel > a particle force demo by Tiffany Rayside (@tmrDevelops) on CodePen.

Present logically for the concept, not for the code.

Sometimes, the building blocks of our code do not proceed in the same order as they appear in the file. Do not fall into the trap of always analyzing your code line by line. If it makes sense to build up a concept within the middle, first, go right ahead. Just make sure to present the complete picture at the end, so they can see how it all fits together.

Take this contrived example...

var PrefixTree = function () {

var self = this instanceof PrefixTree

? this

: Object.create(PrefixTree.prototype);

self.root = new Node();

return self;

};

I wouldn't begin by discussing var self and how it makes my PrefixTree factory new agnostic. That's a whole lot of "wtf?" for a reader learning about pseudoclassical instantiation. Instead, I'd begin by explaining that we have some new object, self, which gets a property assigned to it: the result of new Node(). I would probably even omit that first set of lines and save it for a separate section discussion the value of making constructors new agnostic.

As you go along developing your content, it's useful to think about the order in which you should present information. In the next section we'll cover how to frame the development of your content.

Framing

While developing your post, you will benefit immensely from empathizing with your average reader. Understanding where they are coming from will guide how and what you write. Here are some suggestions to find success.

Lay the foundation first.

Programming is a lot like making a house of cards. You need to lay out the first level before you can begin working on the second. It's more like a deck of cards (instead of a building) in that the house can easily be blown over.

You will be served well by taking the time to lay a solid foundation. If you jump to the meat of your work immediately, you run the serious risk of losing the reader. And that's a shame, because I'm sure you have some cool stuff to show off.

Even consider working with a simpler example to begin with. A tutorial on currying, for instance, could jump right into the implementation of a custom curry function (not native to JavaScript). That works, but it's not fun for many. If a person wants the answer right away, they can navigate your table of contents or skim the headers to get there quickly.

Instead, you begin with a simple example of what currying does in the first place.

function sumWith(a) {

return function(b) {

return a + b;

}

}

var fivePlus = sumWith(5);

fivePlus(2) // 7

After laying out the groundwork, you can move on to the more significant pieces of the tutorial. It may be hard work to lay all the foundation necessary, and again there's some fuzziness about what is reasonable to assume in terms of technical literacy, but overall you're better off devoting time to making sure everyone is on the same page.

Empathize with your reader.

Recognize that this space may be confusing and mysterious. Endeavor to make your logic as crystal-clear as possible. Above all, do not say "it's simply ...". These statements make a big assumption that the concept will be as easy for you as it is for the reader. This may not be the case. I'm always perturbed when encountering such statements and finding the concept not simple at all. It makes me wonder if I'm missing something.

One concept at a time.

In a similar vein, endeavor to present one new concept at a time. Doing so reduces the mental load when trying to parse the new block of text. Your job as the teacher is to identify the least code necessary to practice the concept, without introducing a bunch of ancilliary ideas that distract from the main point.

Explain it to a grade-school student.

You can explain the science of DNA to a third grader if you try hard enough. While it may be necessary to assume a certain technical level of expertise for your tutorial, you should still have your logic be understandable by anyone.

Writers often will delve into a concept without context or warning, without something as simple as "now we're going to build the HTML element to receive drag'n'drop files." Engineers often want to just do it without wasting time to explain what they're about to be doing. Thinking your code will be easily self-explanatory is tempting, but rarely true. As the reader you're left behind, guessing at what they were thinking and why they took the next step.

Writing tutorials (that don't suck) takes practice.

There is a lot to think about here. Writing is an art, teaching is an art; with tutorials, you're try to put them together. It's not easy and you won't get everything all the time. So, just get started and keep continuously improving your craft. I hope you've learned something from this post and enjoyed the ride.

(Feedback is always welcome. Think my tutorial sucked and know how to make it better? Let me know in the comments!)